En estos tiempos oscuros, en los que el madridismo se lame las heridas en espera de la Regeneración, el blog donde se reúne su reserva espiritual sigue extendiendo al mundo universo la verdad sobre las insidias que sus enemigos han vertido a lo largo de los años. Llegamos así al quinto y escalofriante capítulo de Whiter than you think, que narra cómo nos robaron la 6ª Copa de Europa.

Artículo original: Anti-Barcelona.com

Traducción: El Socio

What you may have heard:

Real Madrid was always favored by UEFA so they could achieve the great successes of their golden era. On the opposite, Barcelona would always be stopped on their tracks by UEFA rulers and referees to prevent them to reach bigger achievements.

The facts:

At the beginning of the 1960-61 season, Real Madrid was the undisputed top team in the world – After winning five european cups in a row, they had conquered the first Intercontinental Cup, beating Peñarol de Montevideo, the american champion, by 5-1. That season, the world champions were coupled in the European Cup 16 last round with their historical rival, FC Barcelona. No one doubted that the mighty Real Madrid would pass the round, even though Barcelona were champions of Spain. Nevertheless, the performance of not one, but two referees, were to prevent that.

The first match was played in the Santiago Bernabéu on November 9, 1960. With an enthusiast crowd, Real displayed a great gameplay, which put them in advantage 2-1 with two minutes to the end of the match. In that instant the barcelonist Evaristo sent a long pass to the hungarian Kocsis, who was clearly off-side, foul which was signaled by the linesman. The play ended when the Real’s keeper Vicente hastily left his goal and knocked Kocsis down outside the penalty area. Astonishing everyone in the stadium, the english referee, Arthur Ellis, did not only ignore the offside, but also gave a penalty kick for Barcelona. Luis Suárez would take it to put the 2-2 in the scoresheet.

The european papers covered this controversial play. In the Paris-Presse, Louis Neville reproduced these words from Mr. Ellis: «I’m quite sure to have seen my linesman waving his flag, but it was to signal the penalty». Nevertheless, the linesman, Mr. Stewart, told to the same journalist: «It’s obvious. I’ve seen a Barcelona player offside». When he was asked why he hasn’t done anything when the referee gave the penalty, he said: «I thought Mr. Ellis would have a good reason to let the game go on. Thus, I kept my run on and I saw a penalty».

For the second leg, played on the 23rd of the same month in Barcelona, UEFA designed another englishman, Reg Leafe, to referee the match. Though we could consider that Arthur Ellis had made an isolated mistake, Leafe’s performance in Barcelona could hardly be defined as any other thing than a deliberate theft. It’s very hard to find another match in the history of international competition where a referee benefitted more a team over the other. The match was broadcasted in TV, so we’re not talking about some written account – What the spanish and european fans would see were neutral TV images. And this is what happened.

Real started the match playing better than its rival. Nevertheless, it was Barcelona who opened the scoresheet by means of Vergés on the 25th minute, hitting a corner kick. Two minutes later, Canario suffered a penalty in Barcelona’s area and stayed lying in the ground. The ball went to Del Sol, who scored. But the goal wasn’t allowed: Leafe had given a foul… against Real Madrid!

In the second half, Barcelona obtained its second goal at the 68th minute, scored by Evaristo, who beat Vicente with an spectacular low header. Immediately, after the kick-off in the center of the field, Puskas passed to Di Stéfano, who headed to the net. Once more, Real Madrid’s skill had overcome an against goal. But once again, the referee disallowed the goal for Di Stéfaano’s offiside. Unexistent offside – the position of Barcelona’s backleft Gracia validated Di Stéfano’s position.

With 2-0 in the scoresheet, Real Madrid stormed Ramallets’ goal and erased Barcelona from the pitch, despite Pachin playing injured as a right striking winger. In that moment came the play which the press of the time would call «the one-legged man goal»: after a good play of the white team in the right wing, Pachin scored another goal, which was once again disallowed by Leafe.

The next play was a shot by Gento, which surpassed Ramallets, but was taken out of the goal by the defender Gracia, when the ball had trespassed the goal line. Leafe did not only disallow the goal – but he didn’t even consult with the linesman, in a much better position to see the play.

With four minutes to go, Canario got to score, and for the blancos’ astonishment, the goal wasn’t disallowed. Madrid desperately went for the draw, and Marquitos almost scored on the 89th minute. Seeing this situation, the referee decreed the end of the match before the reglamentary time.

Unlike «others», Madrid’s players didn’t fall into hysteria. Despite their understandable anger, they had enough guts to congratulate their rivals. In the tribune, Real Madrid directors, as much hurt -if not more- as the team, didn’t resort to the gesticulation and rudeness that would make that presidential box famous in following decades. All of Europe but England, homeland of both referees, gave notice of the scandalous performance of the judge. «France Soir», in November 26 edition, said «the five-times european champions saved their honor thanks to a goal by Canario in the 86th minute, after the referee, Mr. Leafe, disallowed three goals. The TV broadcast shows that the result of the Barcelona-Real Madrid match was distorted by the referee». All the headlines of the european press said more or less the same thing: «Mourir en Beauté (Dying in Beauty)»; «The great defeated in the Nou Camp was the referee»; «Three goals disallowed: Mr. Leafe, the referee, disqualified Real Madrid from the European Cup»; «Real Madrid players have lost their European Cup, against all logic, in favor of an injustice and being superior to their beaters. They produced better-quality football. They were the exclusive protagonists of yesterday’s show in Barcelona. It was a victory, but not a success. And much less a triumph. All the honors go for the beaten, defeated by a coalition of luck and refereeing. Thus, this is not what Barcelona had dreamed for days, weeks, months, years. They didn’t guess that if some day they went up to the Capitolium, it would be using the service stairs.»

What can explain such q tendentious refereeing against Real Madrid? Although in the moment there could be suspicions about a bribery by FC Barcelona, this isn’ very credible. A more logical explanation would be that UEFA were afraid that, if Madrid kept winning European Cups, the interest in this competition would decrease. Thus, it was in their interest to expel Real Madrid as soon as possible. We can’t neither forget the tense relationships of Santiago Bernabéu with UEFA rulers, which materialized in the later negative of Real Madrid’s president to play the UEFA Cup, considering it a «minor trophy».

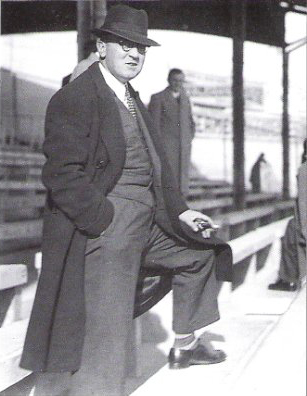

A desolate Di Stéfano with Miguel Muñoz.

Barcelona can’t be blamed for the theft suffered by Real that night without falling into their very same faults. The interesting fact is the little legitimacy of Barcelona when they spread those so-called conspirations which prevent them to be «more than a club». Also very interesting is the different behaviour of both clubs when faced with a damaging refereeing. At no moment Real signaled Barcelona as the culprit, on the contrary. In its informative bulletin, Real Madrid published the following: «… Regarding the national chorus, its unanimity is chilling: Real Madrid didn’t deserve to lose. The chorus includes, and it’s for us an extremely pleasurable duty to signal it, the great catalan press, many of its qualified headlines haven’t hesitated to claim that substantive thruth […], that Barcelona -which has a collossal team that can beat us any day, at their home or at ours-, hasn’t elliminated Real Madrid from the VI European Cup in any place other than the cold -though decisive- official truth of the referees’ reports. In the Bernabéu Stadium and in Nou Camp, two english referees had no mercy of Real Madrid, cucifixying it with absurd rulings, which went from the invention of a penalty to the relentless disallowance of four goals. An authentic conspiracy which could, in less serenes minds than the ones ruling this society, lead to the most direct suspicions. […] Along with the press, the cinema and TV images say today -and will be available to be reviewed now and always- how Real Madrid fell. That’s why honesty’s election gives us as winners. God may favor Barcelona so it gets in the current edition of the European Cup the same glory that in the five previous ones consecrated the clean madridist effort».

Despite Real Madrid’s good wishes, Barcelona lost the final against Benfica. And if anyoned cherished any doubts on who should have won that round, eleven days after the referee’s ransack Madrid beat Barcelona on Nou Camp scoring five goals. Interestingly, on the same season in which Real Madrid suffered its most tendentious refereeing ever, its superiority in the league led their adversaries to create fictitious and artificial controversies about refereeing decisions. It would be in that moment when the black legend about the regime’s favor over Real Madrid would begin to be woven.